Examine the complex relationship between IBD and arthritis

IBD=inflammatory bowel disease.

IBD‑associated arthritis is a distinct disease state with complex intestinal and musculoskeletal manifestations that can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life. Patients with IBD‑associated arthritis require differential treatment approaches; therefore, early recognition and intervention is essential and may be achieved by multidisciplinary co-management between rheumatologists and gastroenterologists.1

Understanding the clinical manifestations of arthritis in patients with IBD

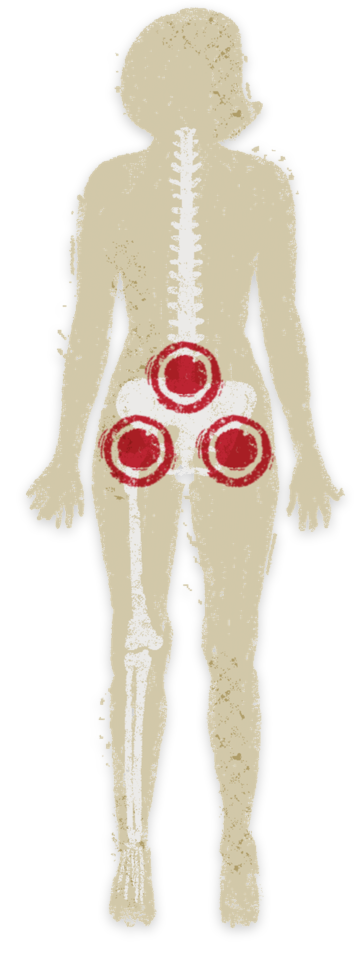

Musculoskeletal pain, including inflammatory arthritis, is the most common EIM in patients with IBD, and may present from multiple sources.2

- Inflammatory musculoskeletal

disease (i.e., SpA)2* -

5% (range: 1%–46%) AS/axSpA16% (range: 1%–43%) pSpA

- Non-inflammatory

musculoskeletal disease3* -

12% (range: 0.4%–23.4%) Osteoarthritis2.2% (range: 0.8%–12%) Fibromyalgia

*Median prevalences from systematic literature reviews are presented. Prevalence ranges are wide due to varying protocols for IBD‑associated arthritis across studies.

AS=ankylosing spondylitis; axSpA=axial spondyloarthritis; EIM=extraintestinal manifestation; pSpA=peripheral spondyloarthritis.

Misconceptions about arthritis presentation in patients with IBD2,4,5:

IBD‑associated arthritis is a distinct disease state that can be clinically differentiated from other seronegative SpA diseases, such as psoriatic arthritis; however, its recognition can be challenging due to its broad and dynamic presentation across different specialties.4-6

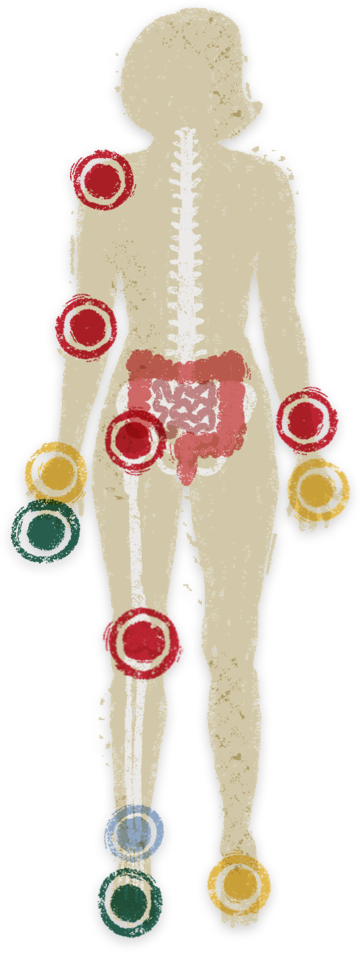

Signs/symptoms of axial arthritis6

- Unilateral or bilateral back pain

- Decreased range of lumbar motion

- Symptoms often precede IBD activity and occur independently

-

Inflammatory low back pain

- Age of onset <40 years

- Insidious onset

- Improvement with exercise

- No improvement with rest

- Pain at night

ASAS inflammatory back pain criteria fulfilled if 4/5 parameters are met7

ASAS=Assessment of Spondylarthritis Society.

Signs/symptoms of peripheral arthritis6

-

Type 1: Asymmetric large joint oligoarthritis (e.g., ankles, knees, hips, wrists, elbows, and shoulders)

- Acute symptoms lasting 6-10 weeks; attacks coincide with IBD relapse

-

Type 2: Asymmetric/symmetric small joint polyarthritis (e.g., hands, feet)

- Chronic course (months to years); independent of IBD activity

-

Enthesitis (inflammation where tendons/ligaments insert into bones, e.g., heel pain)

-

Dactylitis (finger or toe swelling, “sausage digit”)

Clinical characteristics of IBD‑associated arthritis: ASAS-PerSpA study

The observational ASAS-PerSpA study of ~4500 participants identified clinical characteristics of SpA patients with or without concurrent IBD and characterized which factors lead rheumatologists to diagnose IBD‑associated arthritis.5

- Patients with both SpA and IBD (compared to those without IBD) had significantly:

-

Greater

-

Diagnostic delays (5.1 vs 2.9 years; p<0.001)

Less

-

HLA-B27

positivity -

Dactylitis -

Psoriasis

HLA-B27=human leukocyte antigen B27.

-

This study then divided the patients with SpA and IBD into 2 subgroups based on whether the rheumatologist specifically diagnosed the patient with IBD‑associated arthritis vs any other type of SpA with concurrent IBD.5

- Patients with diagnosed IBD-related arthritis (compared to any other SpA with IBD) had significantly:

-

Greater

-

Peripheral

arthritis -

IBD as first

symptom

Less

-

HLA-B27 -

Psoriasis -

Axial arthritis

For the purposes of this study, SpA type was categorized by asking rheumatologists, “In your opinion, which disease better describes your patient?” Answer choices included: r-axSpA; nr-axSpA; pSpA; PsA; ReA; IBD-related arthritis; juvenile SpA; or other type of SpA. All SpA types, excluding IBD-related arthritis, were then categorized as “other SpA with IBD.”

nr-axSpA=non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; PsA=psoriatic arthritis; ReA=reactive arthritis; r-axSpA=radiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

-

Exploring the pathophysiology of IBD‑associated arthritis

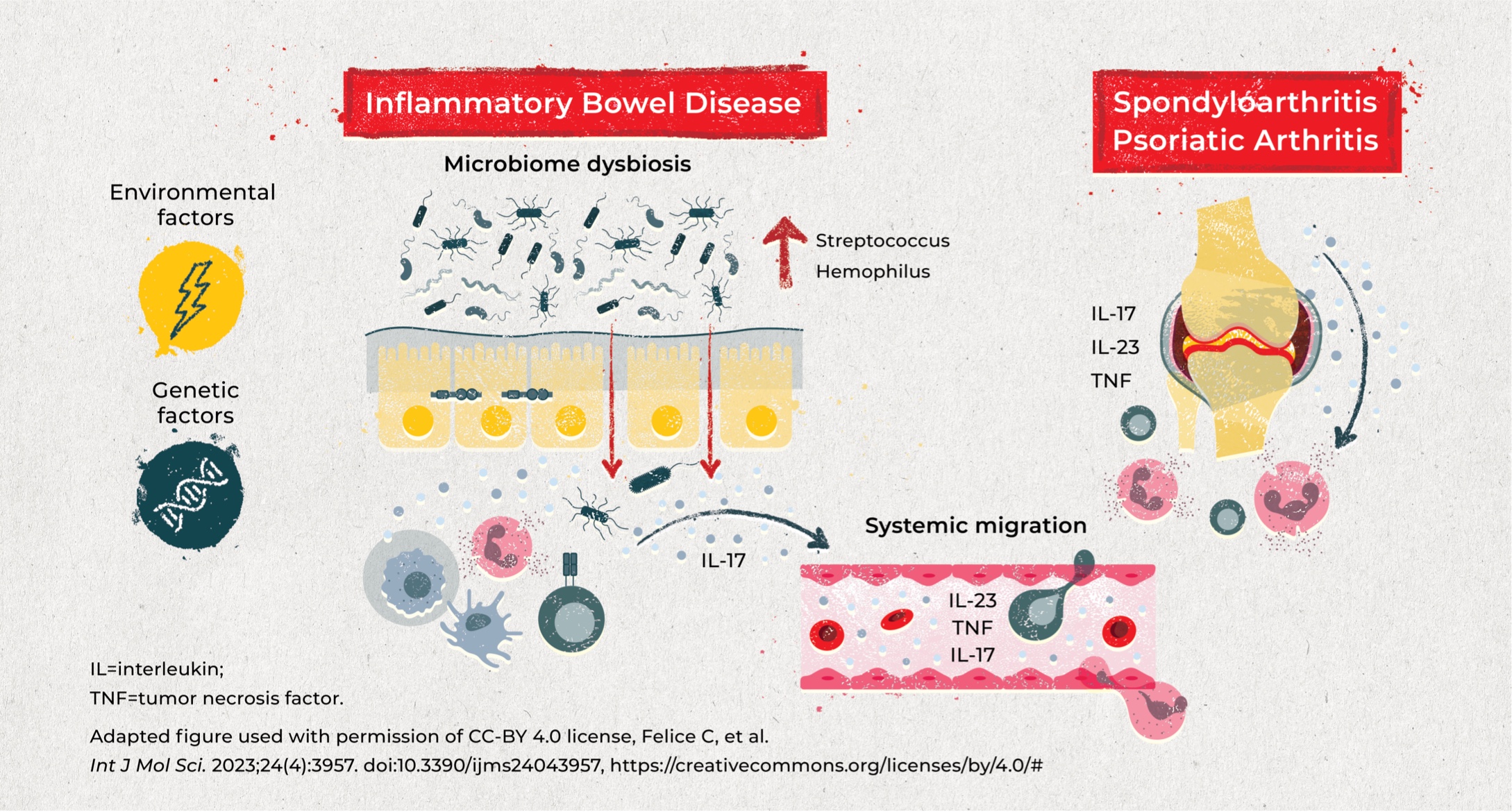

IBD and SpA are both chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with various overlapping factors contributing to the shared pathophysiology.

Genetic and environmental factors in combination with microbiome dysbiosis may impact the integrity of the epithelial barrier, leading to immune cell activation and cytokine production, which migrate between the gut and the joints.8,9

-

Genetic factors

Specific genetic factors may predispose patients to microbiome dysbiosis and trigger arthritis. Most notably, HLA alleles have been implicated in both IBD and inflammatory arthritis:

- HLA-B27 is highly associated with AS (>90% of patients); although the association is weaker in patients who also have IBD (~60%), this association remains high vs the general population (6%–8%)4,10

- Peripheral arthritis in patients with IBD has a strong association with the HLA-DR103 allele (present in ~35% of patients with large joint arthritis vs 1%–3% in the general population)4,11

-

Environmental factors

Although specific data are limited, various environmental factors are hypothesized to be associated with both IBD and SpA, including diet, infection, stress, and particularly smoking12-15:

- In patients with IBD, smoking is associated with a 10% increase in incidence of joint EIMs vs non-smokers, whereas smoking cessation appears to have a protective effect14

- Smoking exposure causes a change in the gut microbiome composition, which may induce intestinal inflammation and further activate inflammatory responses in the joints15

-

Microbiome dysbiosis

Genetic and environmental factors may alter intestinal permeability and microbiome composition, triggering a systemic inflammatory response:

- Patients with active IBD and arthritis have altered inner bacteria networks (increase in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) which are associated with more severe articular disease16

- Potentially pathogenic bacterial genera (Streptococcus and Hemophilus) are elevated in patients with AS and patients with IBD17

-

Cytokines

Both IBD and inflammatory arthritis are associated with various overlapping cytokines, with roles in immunity and epithelial barrier integrity.

- Overlapping cytokines in IBD and SpA include IL-23/IL-12, IL-17, and TNF-α)8,9

The challenges in identifying and managing IBD‑associated arthritis

IBD‑associated arthritis has a significant impact on patient mortality and quality of life. Early recognition and intervention with tailored treatment approaches that consider both disease states would help improve patient outcomes; however, numerous challenges remain.

Recognizing IBD‑associated arthritis as a distinct disease state

There is a need to specifically define arthritis phenotypes in IBD; however, identification and characterization of this patient population is difficult.2,18 MORE

- Heterogeneity in features and presentation

- Lack of recognition of early/key arthritis symptoms in patients with IBD

- Lack of a formal definition, classification criteria, or consensus on a lexicon

Arthritis-specific classification criteria, such as ASAS, have previously been used; however, the applicability of these criteria is unclear and has not been sufficiently evaluated in this patient population.2,18 LESS

Diagnostic delays

Patients with IBD-associated arthritis experience long diagnostic delays (~4–6 years) between the onset of joint symptoms and the diagnosis of arthritis.1,5,19 MORE

Joint pain in patients with IBD may be underrecognized in GI clinics, or may be rationalized as degenerative/mechanical arthritis.1

- Availability of specialists for referrals or the level of experience of the first-line clinician (i.e., in community practice, patients with IBD are usually managed by GI APPs, not IBD specialists)

- Current limited opportunities for effective multidisciplinary management between rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, and APPs

APP=advanced practice provider; GI=gastrointestinal. LESS

Impact on quality of life

Patients with IBD‑associated arthritis report higher disease burden and poorer quality of life outcomes compared to patients with IBD without associated arthritis.1 MORE

- Significantly worse global quality of life across all physical and mental well-being domains

- Greater patient-perceived disease activity

- Considerable work/activity impairment20

No differences in articular activity or quality of life patient-reported outcomes were observed between the arthritic phenotypes (axial versus peripheral). Women demonstrated a trend toward poorer outcomes compared with men. LESS

Importance of a tailored treatment approach

Patients with IBD‑associated arthritis require a tailored treatment approach; however, gaps in available treatments and clinical guidelines pose challenges for disease management.18 MORE

- Direct evidence for clinical guidance and treatment of IBD‑associated arthritis is lacking18

-

Rheumatologists and gastroenterologists differ in treatment approaches:

- Conventional core interventions for each disease aspect have differential mechanisms of action, efficacy, safety, and dosing that require specific considerations and increase the complexity of managing IBD‑associated arthritis18

- Although there are specific therapies that can treat both disease states, some options that are effective in one, may be detrimental to the other19 LESS

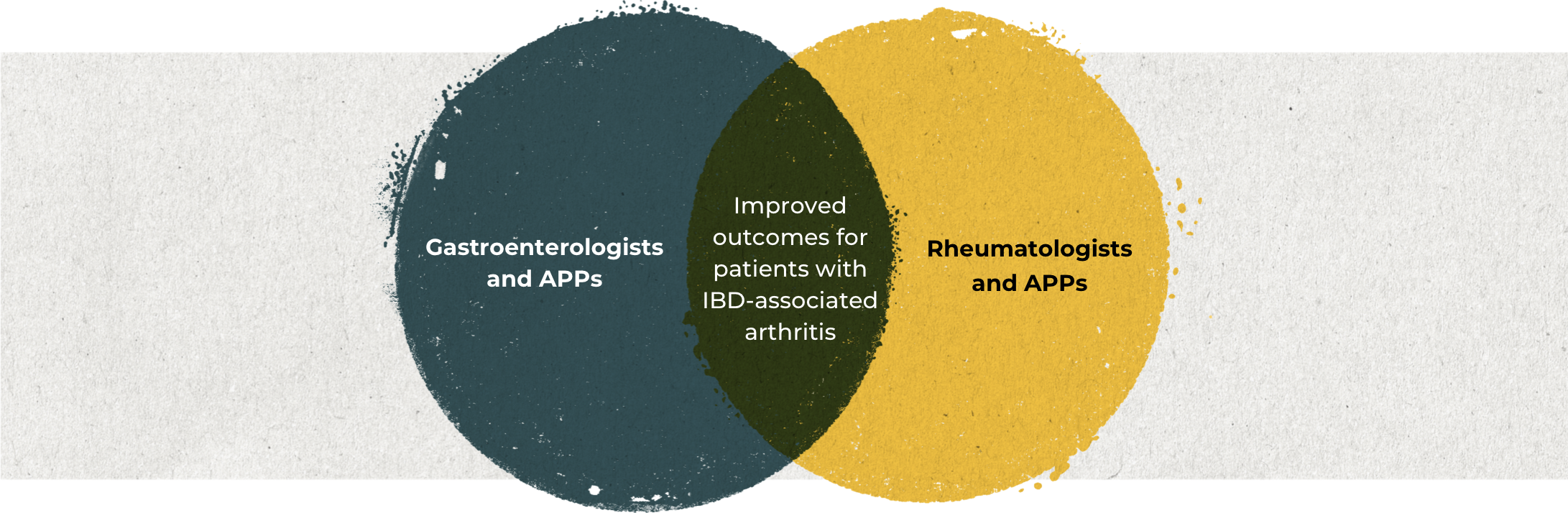

Multidisciplinary collaboration is critical to improving patient outcomes

In order to optimize treatment of patients with IBD‑associated arthritis and improve patient outcomes, rheumatologists and gastroenterologists need to be able to effectively identify factors that prompt referral, and leverage co-management opportunities to provide patients with comprehensive multidisciplinary care.1

See the symptoms that should prompt a referral.

Symptoms to consider when referring a patient

with IBD-associated arthritis18

- Red flags for IBD

-

- Chronic diarrhea for more than 4 weeks

- Abdominal pain for more than 3 months

- Nocturnal diarrhea or abdominal pain

- Rectal bleeding (not due to hemorrhoids)

- Perianal fistula or abscesses, recurrent oral aphthosis

- Unexplained constitutional symptoms:

weight loss, fever, anemia - Family history of IBD*

Refer to a gastroenterologist

- Red flags for SpA

-

- Back pain (for more than 3 months)

- Recurrent or chronic (for more than 3 months) peripheral joint pain or swelling

-

Inflammatory back pain:

- Age at onset younger than 40 years, insidious onset, improvement with exercise, no improvement with rest, pain at night

- Finger swelling (i.e., dactylitis) ever

- Heel pain (i.e., enthesitis) ever

- Family history of SpA†

Refer to a rheumatologist

*First- or second-degree relatives with IBD.

†First- or second-degree relatives with AS, psoriasis, acute uveitis, or reactive arthritis.

Table used with permission of CC-BY 4.0 license, Zioga N, et al. Med J Rheumatol. 2022;33(Suppl 1):126–136. doi:10.31138/mjr.33.1.126, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/#

Become a member of the RheuMuseum and be the first to know about new exhibits

Sign up to stay in the loop on new exhibits about clinical research, important updates, and other educational opportunities.

- Luchetti MM, Benfaremo D, Bendia E, et al. Clinical and patient reported outcomes of the multidisciplinary management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-associated spondyloarthritis. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;64:76-84. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2019.04.015

- Schwartzman M, Ermann J, Kuhn KA, et al. Spondyloarthritis in inflammatory bowel disease cohorts: systematic literature review and critical appraisal of study designs. RMD Open. 2022;8(1):e001777. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001777

- Schwartzman M, Schwartzman S. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(suppl 1):S42. Chron’s & Colitis Congress abstract

- Orchard TR. Management of arthritis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8(5):327-329

- Ono K, Kishimoto M, Deshpande GA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with spondyloarthritis and inflammatory bowel disease versus inflammatory bowel disease-related arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42(10):1751-1766. doi:10.1007/s00296-022-05117-0

- Rodriguez-Reyna TS, Martinez-Reyes C, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Rheumatic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(44):5517-5524. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.5517

- Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl II):ii1–ii44. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.104018

- Gracey E, Vereecke L, McGovern D, et al. Revisiting the gut-joint axis: links between gut inflammation and spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(8):415-433. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0454-9

- Felice C, Dal Buono A, Gabbiadini R, et al. Cytokines in spondyloarthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3957. doi:10.3390/ijms24043957

- Orchard TR, Holt H, Bradbury L, et al. The prevalence, clinical features and association of HLA-B27 in sacroiliitis associated with established Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(2):193-197. doi:10.llll/j.1365-2036.2008.03868.x

- Orchard TR, Thiyagaraja S, Welsh KI, et al. Clinical phenotype is related to HLA genotype in the peripheral arthropathies of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(2):274-278

- Generali E, Bose T, Selmi C, et al. Nature versus nurture in the spectrum of rheumatic diseases: classification of spondyloarthritis as autoimmune or autoinflammatory. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(9):935-941. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.04.002

- Abegunde A, Muhammas BH, Bhatti 0, et al. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: evidence based literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(27):6296-6317. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6296

- Severs M, van Erp SJH, van der Valk ME, et al. Smoking is associated with extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(4):455-461. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv238

- Shapiro H, Goldenberg K, Ratiner K, Elinav E. Smoking-induced microbial dysbiosis in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2022;136(18):1371-1387. doi:10.1042/CS20220175

- Cardoneanu A, Mihai C, Rezus E, et al. Gut microbiota changes in inflammatory bowel diseases and ankylosing spondylitis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021;30(1):46-54. doi:10.15403/jgld-2823

- Sternes PR, Brett L, Phipps J, et al. Distinctive gut microbiomes of ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease patients suggest differing roles in pathogenesis and correlate with disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):163. doi:10.1186/s13075-022-02853-3

- Zioga N, Kogias D, Lampropoulou V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-related spondyloarthritis: the last unexplored territory of rheumatology. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2022;33(suppl 1):126-136. doi:10.31138/mjr.33.1.126

- Conigliaro P, Chimenti MS, Ascolani M, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary approach in enteropathic spondyloarthritis patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(2):148-190. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.002

- Ramonda R, Marchesoni A, Carletto A, et al. Patient-reported impact of spondyloarthritis on work disability and working life: the ATLANTIS survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:78. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-0977-2